Marcia Brooks, 45, lives in Deerfield Beach with her two teens and two small dogs, Paco and Oliver. (Photo by Mc Nelly Torres)

Banks Fail To Protect Consumers From ATM Crime, FCIR Investigation Finds

By Mc Nelly Torres

Marcia Brooks, a single mother of two teens, was heading to her Walgreens job one Monday evening when she stopped at her neighborhood bank in Pompano Beach to make a deposit on the ATM.

It was around 10 p.m. when Brooks parked her Ford Focus on the curb about 10 feet away from the Wells Fargo ATM, instead of using the dimly-lit parking lot.

As she completed the $160 cash deposit, Brooks heard a vehicle rushing towards her. The red Chevrolet stopped abruptly, blocking her car. A man wearing a stocking to conceal his face and armed with a handgun jumped from the passenger’s seat and demanded money while pointing the gun to her face.

Brooks froze.

“I knew there was no place for me to go,” said Brooks. “It was terrifying.”

RelatedThis report was produced in partnership with NBC6 South Florida. |

The robber pressed the gun against her neck and ordered Brooks to make a withdrawal. She quickly made a transaction to withdraw the money she had deposited minutes before.

The 45-year-old prayed for someone to rescue her even though she knew that was unlikely: the building’s back blocked the view from busy Federal Highway, making it difficult for someone to see the robbery in progress.

Automatic teller machines offer consumers around the clock access to bank accounts, but as Brooks found out on July 29, 2012, ATMs are also a magnet for violent crime.

Unlike cases of fraud or identity theft, ATM violent crimes are largely under-reported because nobody tracks them. Not the FBI, the police or the banking industry. What’s more, lax regulations regarding ATM safety are rarely enforced as the banking lobby resists stronger safety measures and tries to keep litigation cases confidential, an investigation by Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and NBC6 South Florida has found.

But media reports show thousands of ATM-related crimes occur in the United States each year. In extreme cases, consumers have become victims of homicide, rape, shootings, carjacking and kidnapping, all for quick cash. In Florida, at least 35 ATM armed robberies, including shootings, carjacking and murder, have been reported since 2011, news reports show.

The most recent of these occurred in Daytona Beach in June, when a former college student pointed a handgun at a woman who was about to make a deposit — as her three children watched.

FCIR analyzed emergency or service calls placed from banks with ATMs in Broward and Miami-Dade counties for the years 2008-2012. Victims, attorneys, crime and security experts were interviewed. The analysis shows that banks with the highest number of reported crimes –including fraud, theft, burglary, and bank robbery — were more likely to have armed robberies at their ATMs.

Wells Fargo said the company is always evaluating the safety and security of ATMs and facilities to ensure customers conduct their business safely. But the financial institution would not say if any security improvements had taken place at the property in Pompano Beach since Brooks was robbed last year.

“We are saddened to hear about this unfortunate incident,” said Michelle Palomino, a spokesperson. “We are not able to provide details of our security procedures, as doing so could jeopardize them.”

Chris E. McGoey, a security consultant and private investigator based in Los Angeles, Calif., says banks don’t want the public to know which ATMs are located in dangerous locations.

“Why is this ATM open at night if all these crimes have occurred?” McGoey asked. “You know that someone is going to die eventually, and if the public knew that a robbery would be more likely to occur at that location at night, would they go?”

Victims and attorneys also cite the following as clear violations of state law: ATMs with missing or damaged mirrors; ATMs with high shrubbery; and ATMS with poor lighting in parking lots.

In Florida, all financial institutions with ATMs must provide:

• Adequate lighting during hours of darkness in parking, access area and around ATMs;

• Reflective mirrors to allow customer a rear view while using the machine;

• Any landscape, vegetation or other physical obstructions in the area shall not exceed three feet high and must be well lit for any open and operating ATM.

The Florida Office of Financial Regulation (OFR) is the state regulatory agency for financial institutions in the state, charged with inspecting state banks and enforcing these minimum ATM safety requirements. But it’s difficult to know if the agency is enforcing these regulations because as of October 2013, no citations have been issued to any of the 250 Florida state banks going back to 2009.

This is even though the state agency has 118 full-time inspectors in charge of visiting all state banks every 18 months, according to Tiffany Vause, a spokesperson with OFR.

As for the thousands of national bank locations in Florida, it’s difficult to know if banks are meeting these minimum standards. Federal regulators told FCIR and NBC6 the inspections are confidential.

Nor are OFR citations public when issued at any state bank. FCIR and NBC6 requested to follow an inspector and to review inspection records, but were denied.

“Books and records of financial institutions are confidential and may only be made available for inspection and examination to limited individuals in certain explicit circumstances,” read a letter issued by the OFR. It went on, “A review of the records by a reporter accompanying an examination team would involve unlawful disclosure of confidential information that is a 3rd-degree felony.”

The Florida banking lobby, which has contributed at least $9 million to state legislators since 1996, opposes stronger safety measures. It often tries to shift the responsibility to individual consumers, attorneys tell FCIR. As victims of ATMs crimes hold banks accountable in civil court each year, the banks continuing strategy is to settle cases to avoid trials. In that way they keep information confidential and away from public disclosure, critics contend.

Jason Turchin, a Weston-based attorney who represents victims of ATM crimes in Florida, Washington D.C. and New York, says sometimes he agrees to settle cases because his clients want closure after enduring the trauma of a violent crime.

“Unfortunately, the only way banks take responsibility is by writing a check,” said Turchin, who early this year settled a case for a woman who was sexually assaulted at an ATM in Tampa.

An ATM timeline

The first automated teller machine was introduced in New York City in 1969. By 2009, there were 401,500 ATMs in the U.S., the most recent data available, according to Tremont Capital Group, an investment banking organization. No entity tracks the numbers in Florida, where ATMs are not only located at banks but also shopping centers, supermarkets and gas stations.

As robberies and other violent crimes at ATMs became more prevalent in the 1980s, New York City and Los Angeles took the lead in approving laws to improve security. At least 12 states, including Florida – have enacted similar minimum requirements since the 1990s.

Growing concerns about violent crimes at ATMs prompted several U.S. legislators to file House Bill 3662 in 2002. Dubbed the ATM Consumer Protection Act, it would have required the Federal Reserve System to adopt mandatory minimum requirements, such as lighting, surveillance cameras, maintenance of surveillance records and alarm systems, for the security of ATMs. Owners would have to develop measures to discourage robberies and assist in identifying perpetrators. But the proposed measure died in subcommittee.

Battle lines drawn

While critics continue to point to ATM crime as a public safety issue, the banking industry, they say, has ignored this problem for years because they don’t want to institute costly corrective measures.

Alex Sanchez, president of Florida Bankers Association, says financial institutions take safety seriously and are doing everything they can to follow state rules.

“Our job is to provide a safe and good experience for our customers,” Sanchez said. “Obviously they want the convenience. We take safety very seriously.”

John Leighton, a Miami attorney, has tried violent crime and negligent security cases for 27 years.

But John E. Leighton, an attorney based in Miami and the author of Litigating Premises Security Cases, disagrees.

“They say consumers should know it is dangerous,” Leighton said. “But when a consumer goes to the ATM and they see light and mirrors, they think that it must be okay because the bank is providing that convenience.”

Leighton, who has tried violent crime and negligent security cases for 29 years, represented the family of Alfred L. Gordon Sr., an Orlando police officer. He was off duty when he was shot and killed in 2007 during a robbery at an ATM.

The Gordons filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the two men convicted for Gordon’s murder; Bank of America; and the shopping center where the bank was located.

The bank and the shopping center settled out of court for an undisclosed amount while a jury awarded the family a whopping $24.5 million that targeted any future earnings his killers might collect.

In the Gordon case, Leighton says, the ATM had poor lighting, mirrors were missing and it was located in a high-crime area.

“Florida regulations have no teeth,” he said, “and the only way to seek justice for victims is through the civil court system.”

No data to analyze

Joseph Gleason, a Lakeland attorney, had a simple question. Why he could go online and search for sex offenders in any neighborhood in Florida, but he couldn’t find the dangerous ATMs?

He had seen the headlines after ATM users were robbed at gunpoint, assaulted, sometimes killed. Gleason, who used to work in the citrus industry in the 1990s, traveled the roads in Florida and he often used ATMs.

Last year, Gleason began the arduous task of contacting law enforcement agencies in all counties in the state with the sole purpose of filing open records requests for crimes related to ATMs.

But soon, Gleason discovered that ATM-related crimes are not documented like other crimes, such as burglaries, homicides or assault.

Every year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation publishes the Uniform Crime Report which has become the official measurement of crime in the U.S. But even as it documents murder, manslaughter, forcible rape, burglary, aggravated assault, larceny, arson and motor vehicle theft, there’s no category for ATM-related crimes.

“I never thought it would be this difficult,” Gleason says. “I thought this would be a piece of information that law enforcement would want to have.”

In fact, when the Federal Trade Commission attempted to study this issue, a mandate of the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (CARD), the agency couldn’t collect data pertaining to ATM crimes.

Despite the dearth of data, Rob T. Guerette, an assistant professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Florida International University in Miami who has studied this issue, says anecdotal evidence suggests that there’s a growing ATM crime problem.

“Nobody is taking the leadership to systematically record the ATM phenomenon,” Guerette says. “Until we do that, we can’t launch any meaningful initiative to try and reduce it.”

Florida’s Gleason tried one avenue: He drafted proposed legislation to address this issue, and approached several state legislators. But no one has taken interest in it.

The Pompano theft

In the Brooks case, police never found the two men who robbed her in Pompano Beach last year. The robbers took her car keys and left Brooks unharmed standing in front of the ATM at 3885 Federal Highway. Her car was not taken.

Though she’s angry that someone victimized her, she’s grateful to be alive. “They could have shot me or raped me,” Brooks said.

Did she know that the Wells Fargo branch in Pompano Beach has had numerous incidents in recent years, including larceny, fraud and bank robberies in 2008, 2010 and 2012?

Brooks had no idea.

This story was the result of a collaboration between FCIR.org and NBC 6. The story was published on Nov. 30, 2013.

A look at Florida boating regulations and boating deaths

By Mc Nelly Torres

Kenneth Williams worked as a handyman and kept a pole in his pick-up truck just in case he came across a good fishing spot.

On June 20, 2011, Williams grabbed that fishing pole and his oldest son, 9-year-old son Kenneth Jr., and headed from their three-bedroom home in Pompano Beach to the blue waters of the Atlantic Ocean. They were going fishing at Hillsboro Inlet with one of Williams’ friends, David Goodrum.

Then, sometime after 9:30 p.m., tragedy struck. Williams’ 15-foot Cobia was taking on water; it was sinking slowly into the cool, dark waters. Williams, his son and Goodrum were forced into the Atlantic.

Wearing life jackets, Kenneth Jr. and Goodrum swam north to the seawall, where they were rescued. But Williams wasn’t with them. The 36-year-old father hadn’t slipped on his life jacket and was swept away by the strong ocean current.

Kenneth Jr. called his mother around 10 p.m. Dad’s drowning, he told her.

“I knew he was gone the minute we got there,” Johanna Williams recalled. “There’s no way he could have survived that. Not the way the water was going.”

Her husband’s body was found the next day.

Williams was one of 67 people killed on Florida’s waterways in 2011, the most recent year for which data is available, according to an analysis by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and NBC6.

For years, due in part to lax regulations on safety equipment and few mandates for formal boating safety education, the Sunshine State has led the nation in boating-related deaths and injuries. The Florida Legislature has failed to address the state’s hazardous waters through additional safety requirements and mandated boater education, because year after year, the $10.3 billion Florida boating industry and the state’s boating constituents have pressured legislators to keep safety regulations to a minimum.

“Unfortunately, more innocent boaters will continue to lose their lives and their grieving family members will continue to ask, ‘Why?’ ” said Pamela Dillon, education director for the National Association of State Boating Law Administrators, a Kentucky-based organization that advocates for boating safety training. “Our elected representatives are the only ones who can answer that question.”

Lax Regulation

With 2,000 marinas, 1,700 miles of rivers, more than 3 million acres of lakes and 8,000 miles of coastline, the longest of any state in the union, Florida is a boating heaven.

The Sunshine State has more boats registered than any other state, with nearly 1 million vessels including houseboats, sailboats, powerboats, airboats and canoes and kayaks. The top four counties for boating in Florida are Miami-Dade, Pinellas, Lee and Broward, based on boat registration numbers.

In addition, more than 300,000 unregistered boats use Florida’s waterways, and according to a 2011 U.S. Coast Guard survey, 2.5 million households in the state are active boaters.

Florida’s marine industry is the largest in the country. With an economic impact of $10.3 billion, the industry employs about 83,000 Floridians.

In 2011, the most recent year for which state data is available, 67 people were killed in boating accidents in Florida, a 24 percent increase since 2008, when 54 boaters died. Boating injuries also increased 12 percent during that time period, with 431 in 2011, up from 386 in 2008.But every year dozens of people are killed and hundreds injured on the state’s waters in accidents that may have been avoided had boaters received safety education and used safety equipment such as life jackets.

Nationwide, 758 people died in boating accidents and 3,081 people were injured in 2011.

Boating accidents occur for a variety of reasons, including carelessness, speeding, inexperience and intoxication. In 2011, 32 of the 67 boating fatalities in the state were of people who fell overboard and drowned. Over three-quarters of those drowning victims were not wearing life jackets.

According to state data, the most likely to die on the Sunshine State’s world-famous waters are men 35 and older who are not wearing life jackets and have no formal boating safety education.

Most of these deaths were avoidable, according to Pamela Dillon of the National Association of State Boating Law Administrators.

“If you mandate people to wear a life jacket, they might not understand why they need to do that,” Dillon said. “But when you educate them, we have a chance to influence their behavior.”

Florida only requires education for boaters born on or after Jan. 1, 1988, a percentage of today’s boaters so small that the law is without much impact in practice.

Five states – Connecticut, Alabama, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and New Jersey – and the District of Columbia require all boaters to take boating safety classes. Three other states – Washington, Virginia and Hawaii – have passed laws that will ultimately require safety education of the majority of boat operators.

In Florida and elsewhere, boating regulations, including mandating safety equipment and education, are often met with resistance from the boating industry, which fears that additional regulations will discourage boating, costing jobs and economic activity.

Michele Miller, executive director of Marine Industries Association of Florida, said regulations as simple as requiring life jackets when aboard recreational vessels would dissuade people from taking to the waters.

“They are hot and uncomfortable,” Miller said of life jackets.

No state requires all boaters to wear life jackets at all times. Connecticut and Pennsylvania, for example, require boaters in small vessels to wear them at all times only during cold-water months.

That life jackets are hot and uncomfortable isn’t in dispute, but no studies support Miller’s and the industry’s contention that requiring life jackets will discourage people from using boats. No one from the industry could provide evidence to support that assertion.

A three-year study by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at four lakes in Mississippi, however, suggested the industry’s claim is incorrect. During the study period beginning in 2009, boaters at those four lakes were required to wear life jackets. The safety mandate did not result in decreased use of the lake or affect local commerce. The number of annual boating deaths also decreased at those lakes when life jackets were required.

Industry Influence

Charles Flaxman is a Hollywood attorney who has represented boating accident victims for 30 years. He believes the boating industry is standing in the way of commonsense laws that would protect Florida boaters.

“Unfortunately, just as with the issue of gun regulation, it’s all about the lobby and the money,” Flaxman said. “But it’s also about politicians wanting to stay in power while being influenced by lobbyists, who tend to go against regulations.”

Drawing on years of data showing that boating experience alone did not reduce the risk of boating accidents, the Boating Advisory Council encouraged state lawmakers in 2009 to increase the age of boaters required to take safety education courses.Support for Flaxman’s claims can be found in how elected officials in Tallahassee have responded to recommendations from the Florida Boating Advisory Council, an 18-member board created to review boating-related issues and make recommendations to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the state agency that polices Florida’s waters.

“Our proposal was to increase the age in five-year increments each year,” said Capt. Richard Moore of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and a staff member of the Boating Advisory Council. Under current law, only boaters 25 years old and younger must take safety education courses to be licensed for Florida’s waters.

Florida’s politically active boating industry, which has donated nearly half a million dollars to the campaigns of state legislators since 1996, quickly and forcefully opposed the recommendation.

Former state Sen. Lee Constantine, R-Altamonte Springs, then chair of the Environmental Preservation and Conservation Committee, sponsored a bill that included the Boating Advisory Council’s recommendation to require safety education for more boaters.

“I didn’t have the votes,” said Constantine, now a county commissioner in Seminole County. “I’m not saying that it was the right thing to do, but what I’m saying is that it wouldn’t pass.”

Beginning in 1999, the marine and boating industry had given $5,100 in campaign contributions to members of Constantine’s committee, which stripped out the provision that would have required more boaters to take safety courses.

Former state Sen. Carey Baker, R-Eustis, then the chair of the General Government Appropriations Committee, co-sponsored the bill with Constantine. He said the boating industry didn’t influence his vote because the bill was amended before reaching his committee. Baker had received contributions from various industry interest groups totaling $3,000 since 2005.

“There’s a thousand reasons why a bill would be amended or die,” said Baker, now the property appraiser in Lake County.

At the end of 2009 session, and without much notice, the weakened legislation became known as the Osmany “Ozzie” Castellanos Boating Safety Education Act, named after a 23-year-old Miami lifeguard who died on July 8, 2007, after he was thrown from a 27-foot boat carrying 12 people. He was not wearing a life jacket.

Isabel Castellanos, the young man’s mother, was disappointed that a bill named after her son would do so little to make Florida boaters safer.

“I wasn’t pleased with what the Legislature approved,” said Castellanos, who was not invited to speak with lawmakers in Tallahassee. “I wish it was stronger.”

Since current Florida law requires only boaters born on or after Jan. 1, 1988, to take boater safety courses, at least another decade will have to pass before the law catches up to the majority of the state’s boaters, who are typically in their 30s and 40s.

“If the state laws don’t require those people to be educated, then you miss the target,” said Jeffrey N. Hoedt, who heads the Boating Safety Division of the U.S. Coast Guard. “You didn’t get the people who most need that education.”

After the Accident

Sitting in her home on a leather couch next to a picture of Kenneth Williams, Johanna Williams doesn’t like to dwell on what went wrong the night her husband of 11 years drowned off the coast of Pompano Beach.

“I try not to talk about what happened. It doesn’t help them,” she said, referring to her sons, and then paused. “It doesn’t help me.”

Kenneth stored a life jacket on his boat, but he never wore it. He also never took boating safety courses. In that way, he was the typical Florida boater, according to government data.

Williams, 36, works today as an office manager for a physician in Hollywood and raises her two sons, Kenneth Jr., now 11, and Vicente, 9, as a single mother. She admits that her husband might have survived his boating accident on June 20, 2011, had he worn a life jacket.

“People need to respect the water and understand what they are doing to make sure they are safe,” Williams said. “The lifejacket is there for a reason.”

This story was part of a collaboration between Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and NBC 6 in Miami. The story was published April 30, 2013.

13th Grade: How Florida Schools Are Failing To Prepare Graduates For College

By Mc Nelly Torres and Lynn Waddell

Florida’s K-12 public education system has graduated hundreds of thousands of students in the past decade who couldn’t read, write or solve math problems well enough to take some college-level courses.

Florida’s 28 public community and state colleges are required to accept anyone with a high school diploma or G.E.D.More than half of high school graduates who took the college placement test in the 2010-2011 school year found out they had to take at least one remedial course in college to boost basic skill. These students couldn’t pass at least one subject on the placement exam used to assess the abilities of incoming students.

Students taking remedial classes have a harder time getting through college. They must pay for — and the state must subsidize – these basic-skills courses. They do not receive credit toward graduation for remedial classes, and can’t take courses that do count for credit until their skills improve. The result for these students is a longer path to graduating college.

Many of those students never complete their studies.

The need for remedial education is a nationwide problem. But it’s a significantly worse problem in Florida than elsewhere, despite the state’s reputation as a pioneer in overhauling K-12 education.

Some 54 percent of Florida students who took the state college placement test need remedial work in at least one subject. The national average for first-time students needing remediation is 40 percent.

Demand for remedial courses in Florida has doubled since 2007.

Reducing the number of unprepared students in Florida is critical to the state’s economic recovery for several reasons:

- Remedial education increases the cost of a college degree to students and taxpayers.

- Research shows that students who take remedial classes are less likely to graduate from college than those who arrive ready for college-level work.

- Florida’s economy needs more college-educated workers.

- Without a college degree, workers earn lower wages and contribute less in taxes.

National educators are watching how Florida addresses this problem. The Sunshine State has one of the largest community and state college systems in the country. Randall W. Hanna oversees it.

“There is a cost, a cost to the state, a cost to the student. There’s a cost of time,” said Hanna, chancellor of the Florida College System, which does not include the state’s four-year universities. “We all know if they go into the lower-level math class, they have less of a chance to make it all the way through. We have a real incentive from a cost standpoint to reduce the number of students in developmental education and to make sure they are college ready when they come to our system.”

The Economy’s Effect

There are many factors behind the growing crisis of remedial education at Florida’s community and state colleges. Two of them stand out.

One is the Great Recession. The persistently weak job market has produced a surge of displaced older workers at community and state colleges. The number of students aged 20 and older grew by 63 percent between 2003 and 2011. Many of them have been encouraged by the increased availability of federal financial aid.

Some of these older students are going to college for the first time or finishing degrees they never completed. Others are going back to retrain for a different career. Either way, their basic skills tend to be rusty. Older students accounted for 85 percent of those taking remedial courses at Florida’s state colleges in 2010-11.

The subject these students need the most help with is math. Four of every five first-year, full-time students over age 20 had to take remedial math courses, according to the 2011 Florida College System Readiness report using 2009-10 data. For those age 35 and older, the rate increased to 90 percent.

A Skills Gap

The other big factor is more endemic to public education in Florida. Essentially, there

is a disconnect between what students are learning in K-12 schools and what they need to succeed once they get to college.

For more than a decade, under the auspices of reform, Florida has been making dramatic changes to primary education. That included changes in curriculum and graduation requirements aimed at improving student performance in core subjects like reading, math, writing and science.

Standardized tests became more important. The Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, or FCAT, became more than a measure of student performance. Scores became a determinant of how much state funding schools received or whether they could remain open at all. Starting this year, scores help determine teacher pay.

The overriding goal of these changes was to increase the high school graduation rate – and they did. Though Florida has changed the way it calculates its graduation rates, the rate has risen both before and after the change.

But as it’s turned out, increasing the number of high school graduates is not necessarily the same thing as producing more students who are ready for college.

Policy makers have known this for a while. In 2006, the state Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, the research arm of Florida Legislature, found the state’s effort to improve K-12 education hadn’t improved college readiness among students.

At that time, the state agency recommended bridging what it called a “curriculum gap” – the difference between what high school students are taught and what they need to know going into college. Among the problems the OPPAGA report noted included the lack of rigorous high school graduation requirements that go hand-in-hand with college expectations and the need to integrate mathematics and reading to reinforce other courses such as social studies, science and electives.

Measures have only recently been implemented under legislative mandate.

Some education experts lay the blame on the FCAT. Critics say the FCAT’s outsized importance leaves schools little choice but to teach to the test. One of them is Bob Schaeffer, the public education director for the National Center for Fair & Open Testing. He contends that the test interferes with the ability of public schools to prepare students for college.

“When K-12 classes focus on preparation for a narrow, flawed FCAT exam, students are denied the opportunity to master the more sophisticated content and higher-level thinking skills they need to succeed as undergraduates or in the workforce,” Schaeffer said. “The huge percentage of Florida high school graduates who must take remedial courses in college is yet another example of the failure of FCAT-driven public education.”

Matthew Ladner disagrees. He’s a policy and research adviser for Jeb Bush’s Foundation for Excellence in Education, an organization that promotes nationally some of the changes Bush pushed in Florida while he was governor – like increasing emphasis on FCAT scores. Ladner said Florida’s public education has made significant gains in the past decade, thanks in part to high-stakes testing.

“I think people are throwing out the baby with the bath water,” Ladner said. “If you think about what Florida was like before the FCAT, Florida was one of the lowest-ranked states in the country on NAEP.” The NAEP is a national assessment provided to students in grades, 4, 8 and 12 to track student academic progress over time.

To some degree, according to Ladner, Florida’s public education system may be a victim of its own success. He credits the FCAT for increasing the number of high school graduates. Ladner sees it as not altogether unexpected that some of those students would struggle at the college level.

“When you have a substantial increase in graduation rates and you have an increase of kids taking college placement exams, some of these problems would become natural,” Ladner said, referring to the large number of students who can’t pass the college placement exam. “It’s not to diminish that remediation is a problem.”

The Search For Solutions

Florida has begun to address the remedial education problem. In fact, the number of high school students who are prepared for college work has improved some 10 points since 2003 when 64 percent of high school graduates failed at least one subject on the college entrance exam. Still, state education officials acknowledge that the improvements have fallen short of what’s necessary.

Recent legislative changes have taken aim at the problem. The changes include a creating a new college placement test to identify which subjects current high school students need help with before they get to college; increasing the amount of math instruction high schoolers are required to have in order to graduate; and evaluating students’ college readiness before 12th grade.

Florida also is moving away from the FCAT toward something called the Common Core State Standards. These are academic standards for K-12 students that are supposed to be more aligned to college standards. Forty-five states and the District of Columbia have signed on to the new standards. New curriculum and assessments are being created for Florida based on these standards.

The Florida college system also is revamping remedial courses themselves. The goal is to use computerized classes and other targeted teaching techniques aimed at teaching students the skills they need to continue their college programs. But college educators can do little to prepare students before they reach their campuses.

That’s the point Lenore P. Rodicio repeats over and over again when she speaks at public events. Rodicio is the Vice Provost for Student Achievement Initiatives at Miami Dade College. At her school, 63 percent of high school graduates take at least one remedial course upon enrollment. As Rodicio sees it, receiving a high school diploma today should mean a student is ready for college.

“It’s the case for some students now,” Rodicio said, “but not for everybody.”

This award-winning series, exploring the growing need for remedial education among Florida’s high school graduates and older students, were published throughout December, 2012.

13th Grade: More Florida Students Than Ever Before Struggle With Math

By Mc Nelly Torres, Lynn Waddell and Sarah Gonzalez

Wendy Pedroso has never liked math, but for most of elementary school and middle school she got B’s in the subject. It wasn’t until ninth grade at Miami Southwest Senior High School, when Pedroso took algebra, that she hit a wall. In particular, she struggled with understanding fractions.

Pedroso sought help from tutors, took algebra again over the summer and passed. She went on to graduate from high school in 2011.“I kept getting stuck in the same place,” Pedroso, 20, recalled recently. She failed the class, and worried that she’d never get to go to college.

Pedroso enrolled at Miami Dade College’s campus in Kendall. Like all of Florida’s community and state colleges, Miami Dade accepts anyone with a high school diploma or G.E.D. But students must take a placement test to assess their basic skills. Pedroso’s struggles with math caught up with her again: She failed the math section of the test.

It meant that she had to take a remedial math class. The course cost Pedroso $300 like any other class at Miami Dade College but did not count as credit toward graduation. Although she could take college-level courses in other subjects, Pedroso couldn’t begin taking college-level courses in math until she passed the remedial course.

Pedroso was embarrassed.

“I thought that it was going to be very hard to get through college,” she said.

Across Florida, remedial classes at community and state colleges are full with students like Pedroso. More than half of the high school graduates who took the college placement test had to take at least one remedial class. And while many of those students struggle with basic reading and writing skills, the subject they’re most unprepared for in college is math.

In the 2010-11 school year, some 125,042 Florida college students needed to take a remedial math class, an investigation by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and StateImpact Florida has found. That number has been growing for some time, and is more than double the number requiring remedial classes in reading (54,489) or writing (50,906).

Much of the growth in remedial math classes comes from students age 20 and over, who have gone to college amid a tough job market. Far removed from the math drills of their youth, their basic skills have gone rusty, if they had them to begin with.

But the math crisis is also acute among students coming to college straight out of high school. Some 44 percent of high school graduates who took the Florida College System’s entrance exam failed the math section in 2010-11. Less than a third failed in reading and writing.

“I don’t know what happened with these people that come from high school,” said Isis Casanova de Franco, a remedial math professor at Miami Dade College. Casanova de Franco said her granddaughter in second grade can add but many of her college students cannot. “It’s very difficult to understand that they don’t even know how to add or subtract whole numbers.”

A national problem

The situation in Florida is similar to what’s happening across the United States. A 2010 Columbia University study of 57 community colleges in seven states found that one in two incoming students needed to take remedial math courses.

Another study by Harvard University researchers looked around the world. It found that only 32 percent of U.S. high school students graduating in 2011 were proficient in math. Of 65 nations that participated in the Harvard survey, the U.S. ranked 32nd.

Vinton Gray Cerf, an Internet entrepreneur quoted in the Harvard report, said the U.S. is not producing enough innovators because of a deteriorating K-12 education system. He also blamed a national culture that doesn’t value engineering and science.

The culture problem is a deep one and won’t be easy to solve. A number of Florida college students interviewed for this series, including Wendy Pedroso, quickly volunteered that they “hate” math. Many of Florida’s public school students never master basic math skills early in their education, creating a deficiency that causes them to struggle with the subject throughout their educational career.

Jakeisha Thompson, a math instructor at Miami Dade College’s downtown Miami campus, sees it every day.

“What I found with those students is that many of them have had a hatred for math for as long as they can remember,” Thompson said. “And it goes all the way back to elementary school.”

David Rock, dean of the school of education at the University of Mississippi and a former middle and high school math teacher, said cultural antagonism toward math also affects parents’ expectations.

“People don’t want to say ‘my child is illiterate,’ but they have no problem to saying ‘my child is not good at math,’” Rock said. “It has become socially acceptable, and we have to do something before it gets out of control.”

‘A creative discipline’

Many experts say one answer lies in re-thinking how math is taught in K-12 schools. Math is a challenging subject that requires critical-thinking skills — traits not often emphasized and developed in the U.S. public school system, unlike in China and Japan.

How teachers approach math lessons also is crucial, because they need to make lessons interesting to engage students and help them succeed. Teaching techniques such as memorization and repetition have contributed to math’s reputation as a dreadful subject in the U.S., said Richard Rusczyk, founder of Art of Problem Solving. That’s a school in California that focuses on creating interactive educational opportunities for avid math students.

“Math is a creative discipline,” Rusczyk said. “It’s not fun if you have to memorize it, and that way it’s not easy to learn.”

Rusczyk said many students who struggle with math throughout their K-12 careers are like Pedroso — they never mastered basic math skills. “What I found out by working with high school students is to go back where the problem started,” he said. “Sometimes it’s not algebra but the fact that the student never learned how to deal with fractions.”

The use of calculators in classrooms is part of the problem. Students are allowed to use calculators when taking the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, or FCAT – the test they have to pass in order to graduate from high school.

Casanova de Franco, the Miami Dade College remedial math professor, said many students are using calculators before they’ve mastered basic math skills.

“Calculators are good when you know how to do everything,” Casanova de Franco said. “But it shouldn’t be used to supplement thinking.”

A curriculum gap

Another problem is that high school math programs are not geared toward college readiness. The FCAT, for example, tests only 10th-grade level math skills. The Florida Department of Education says a new test coming in a couple of years will be more aligned to college standards.

And up until now, students have been allowed to graduate high school without taking a math class higher than Algebra 1. This is the last year students will be allowed to graduate high school without taking more advanced classes. The hope is that requiring more advanced math classes will mean more students are prepared for college.

But high school teacher Katerine Santana says that alone won’t solve the problem.

She teaches Algebra 2 at Miami Northwestern Senior High. Like professor Casanova de Franco, she said many of her students can’t add or subtract. This poses a challenge for math teachers because students who have fallen behind and lack foundational skills tend to lose interest in the subject.

“Early on, if we instill that math is part of our daily life, I think that kids are going to have more of a positive attitude towards it,” Santana said. “Because in high school, when they’re juniors and are going to graduate next year, it’s very hard to convince them that this is an important subject.”

Some schools are experimenting with hiring a new kind of math teacher. Traditionally, students in elementary schools received math lessons from generalists, who did not necessarily have any expertise in teaching math. But in recent years, school districts have hired mathematicians and math coaches throughout the K-12 system.

Math coaches work closely with teachers and students to build math skills in the classroom. They give struggling students one-on-one attention to help them focus on areas where they need help and work with teachers to design effective math lessons. Many school districts in Florida hired math and reading coaches when federal economic stimulus funding became available in 2009.

The new hires may help. A three-year study in Virginia that ended in 2008 found that math coaches in elementary school have a positive impact on student achievement over time.

Who’s responsible?

Wendy Pedroso blames the K-12 public school system and her teachers for not preparing her for college. Pedroso admits she became too dependent on calculators in her high school math classes. But she said she was a vocal student in high school and frequently asked questions about algebra and fractions.

“I needed to understand why and how things worked,” Pedroso said of one of her math teachers. “But she didn’t take the time to explain things and moved onto the next subject even if we didn’t understand.”

Maria P. de Armas is assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction at Miami Dade County Public Schools, where Pedroso was a student. According to de Armas, Miami schools have instituted programs to identify students who are struggling with math and other subjects. But de Armas noted that meeting the needs of a diverse and economically depressed population — Miami is the sixth-poorest city in the United States — is challenging.

When asked if she thinks the public school system fails students, de Armas said: “I emphatically feel that we have not failed. I feel that nothing is perfect, and there’s always room for improvement.”

Shakira Lockett, another product of Miami schools, said the onus for learning math ultimately lies with students themselves. Lockett, 22, recently graduated from Miami Dade College after taking seven remedial classes.

Three of those classes were in math. Lockett didn’t blame her teachers. She blamed herself for not working hard enough at math while in high school. “Sometimes I felt lost in math, but I feel that the teachers were OK in public schools,” Lockett said. “I was able to get the proper teaching in the schools. But I think it was up to me also to go home and study. I just hated math so much.”

Wendy Pedroso’s negative attitude toward math has changed a bit. After dropping out of her first remedial math class at Miami Dade College, she passed the lower-level remedial math class last spring among the top students in her class. The extra coursework taught her discipline and studying skills, she said. She has conquered her fears of fractions and doesn’t rely on a calculator anymore.

“I see the difference in my work,” Pedroso said.

While Pedroso hasn’t declared a major, she acknowledged that her experience has given her the confidence to consider choosing a field of study that requires math. She’s considering studying business, criminal justice or advertising.

“I’m not as scared at looking at other areas as I was before,” Pedroso said. “I’ve got a lot of more options.”

13th Grade: In State Community College, A Crisis of Unprepared Freshmen

By Sarah Gonzalez, Mc Nelly Torres and Lynn Waddell

Shakira Lockett was a pretty good student in elementary, middle and high school. The Miami-Dade County native says she typically earned As and Bs in English classes.

She went straight to Miami Dade College. Then, something unexpected happened: She flunked the college placement exams in all three subjects – reading, writing and math. That didn’t mean she couldn’t attend the school; all state and community colleges in Florida have an open-door policy, which means everyone is accepted. But it did mean she had to take remedial courses before she could start college-level work.Math was always something of a struggle for Lockett. Still, she got through her high school exit exam with a passing grade and went on to graduate from Coral Gables Senior High School in 2008.

“When they told me I had to start a Reading 2 and Reading 3 class, I was like, ‘Serious?’” Lockett said. “Because I’ve always been good at reading.”

Lockett, who is now 22, spent a year-and-a half taking remedial classes before she could start her first college-level class to count toward her degree in mass communication and journalism. The seven extra courses cost her $300 each.

Lockett found having to take remedial classes discouraging. “It makes you feel dumb,” Lockett said. “And you ask yourself, ‘Is there something wrong with me?’”

Lockett’s experience actually is quite normal in Florida. In 2010-11, 54 percent of students coming out of high school failed at least one subject on the Florida College System’s placement test, according to an investigation by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and StateImpact Florida. That meant nearly 30,000 students – high school graduates – had to take at least one remedial course in college.

Florida’s remedial education needs are much greater than in many other states. Nationwide, about 40 percent of all first-year students need remedial education before they can enroll in credit-bearing courses, according to the Alliance for Excellent Education, a Washington, D.C.-based policy and advocacy group.

The numbers are worse at Miami Dade College, Lockett’s school. There, 63 percent of high school graduates take at least one remedial course upon enrollment. Many of them are, like Lockett, shocked to find out that they weren’t ready for college despite having a high school diploma.

The Cost of Being Unprepared

There’s a price to all these students showing up at Florida’s 28 community and state colleges unprepared. The students must pay for – and the state must subsidize – the remedial coursework. The costs of remedial education, shared by students and the state, have jumped from $118 million in 2004-05 to $168 million in 2010-11.

Most of the state’s cost is spent on non-traditional students – students who return to college after being out of school for a while. But according the Florida Department of Education, about one-third of the cost of remedial education is spent on students who are fresh out of Florida high schools.

Education experts say part of the problem is that a high school diploma has never been the same thing as a certificate of college readiness. There’s a curriculum gap between what high school students are taught and what they need to know going into college. And it’s been an ongoing problem that state educators have not addressed until recently.

Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush has been a proponent of the state’s high school exit exam – the FCAT. But now the conservative education advocate admits the test was never meant to determine whether students are prepared for college.

“It’s really a gateway to graduate from high school, not to be college ready,” he told StateImpact Florida in an interview.

Bush said it’s evident the test is flawed since many high school students can’t graduate because they can’t pass the FCAT, which only tests 10th-grade level academic skills.

“Or worse yet, as you said, 50 percent of our students need remedial work to be able to take a college course,” he said.

Lenore Rodicio is Vice Provost for Student Achievement Initiatives at Miami Dade College. She said until high school curriculum aligns with college curriculum, state and community colleges need to fill in the gaps by offering remedial courses, also known as “developmental education.”

“One of the downfalls of developmental education,” Rodicio said, “is that students get stuck in a cycle where they don’t pass their courses and have to take multiple semesters of the developmental courses before they go in to college-level work.”

Remedial classes do not count toward a college degree. Each class runs an entire semester. And students cannot enroll in college classes until they pass all their remedial courses. But Rodicio said offering remedial courses allows Florida colleges to keep their doors open and give all students the opportunity to get a college education.

A down side, Rodicio said, is that students who fail a remedial class are less likely to make it to the finish line of graduation.

Inside a Remedial Class

At Miami Dade College, the final project for students in most remedial writing classes is to write a single paragraph by the end of a semester.

“We’re looking to see that students can focus a topic, maintain a main idea, develop that point, support that point, use transitions,” said Associate Professor Michelle Riley. And she said it’s very difficult for many of them.

During a recent remedial reading class, Riley showed students a sentence on the white board.

It read: “The bandage was wound around the wound.”

The professor asked students to read the sentence aloud. Many got stuck on the last word – pronouncing the word “wound” (sounds like “boomed”) the same way they pronounce “wound” (sounds like “ground”).

The course is one step above the lowest remedial reading level offered at Miami Dade College. Students study the difference between denotations and connotation – the difference between a word’s dictionary definition and its cultural or emotional association.

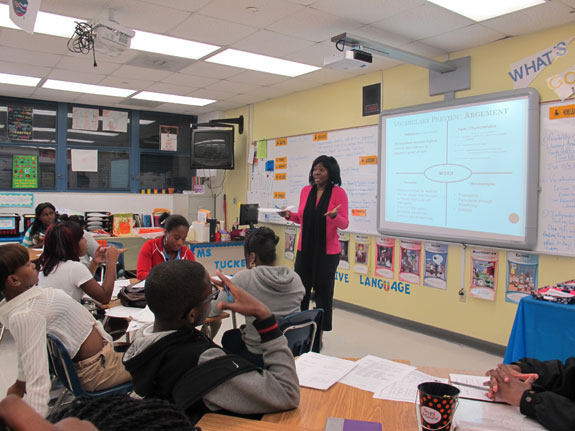

Miami high school teacher Vallet Tucker said she isn’t surprised to hear what students are learning in remedial college courses. She teaches honors English at Miami Northwestern and said her average 10th-grade student reads at a 7th-grade reading level.

“And I have honors students,” she pointed out.

“This is 10th-grade material and they’re not there yet. The vocabulary is not where it should be –the stamina for reading,” she said. “I look at some of my students and say, ‘I wish we could read this novel,’ but they’re not there yet.”

FCAT Focus of Criticism

Standardized testing has been a big part of public education in Florida for more than a decade. The Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test – the FCAT – debuted in 1998. It’s used as a tool to assess high school students, determine their class placement and decide whether they can graduate from high school.

But over time, FCAT has also become a management tool. Students’ scores on that test now determine school funding levels, teacher evaluations, and starting this year teacher pay. FCAT scores also help determine whether a school itself stays open or is shut down for poor performance.

Critics of the FCAT say teachers, under pressure to help students achieve higher test scores, have emphasized test-taking skills over core subject lessons. Students are taught to memorize facts and eliminate answers on multiple-choice questions.

“From the time a child is in kindergarten, every option that a child is given has four answers for which two or three can be easy eliminated,” said Raquel Regalado, a Miami-Dade school board member. “Unfortunately, life doesn’t give you four options for which two or three can be easily eliminated. And that’s the problem.”

The FCAT has become more rigorous over the years in reading, writing and math. But the material doesn’t align with what is tested on the college entrance exam.

Success on the FCAT, the state accountability office found, “does not ensure students are prepared for college-level work.” OPPAGA noted that despite previous reports pointing out the same problems, state education leaders and legislators had not reviewed the effectiveness of the FCAT. Policy makers have understood this for a while. In 2006, the research arm of the Florida Legislature, widely known by its acronym OPPAGA, studied remedial education in community colleges. The study concluded that the FCAT created a disconnect between the skills taught in public schools and those needed in college.

Matthew Ladner, a policy and research adviser for Jeb Bush’s Foundation for Excellence in Education, is a defender of FCAT. He said the test, emphasized when Bush was governor, helped increase the high school graduation rate. In the 2010-2011 school year, Florida graduated the most students, and students of color, in the state’s history. Lander sees it as not surprising that some of those students would struggle at the college level.

“So we should not view the fact that these students then go on to an institution of higher education and have to take a remedial course necessarily as a catastrophic failure,” Ladner said. “This is sort of a process on the way to success in the sense that a lot of those students in Florida higher education institutions today would have dropped out of high school 15 years ago.”

The increasing number of people entering college, he said, may be a factor in rising remedial education numbers.

Damaging Illusion

In Florida, the current situation has contributed to a damaging illusion among many students. Some who excel in public school and do well on the FCAT graduate thinking they are well prepared for higher education, only to find they’re not ready at all.

Shakira Lockett felt she was ready for college. The reality for her, though, was that she needed extensive remedial work at Miami Dade College. She finally completed her two-year journalism program in May – two years later than she’d expected going in.

It wasn’t easy. “I had to push myself where I need to be to make my parents proud of me and to make myself proud,” Lockett said. “Because I really want to be something in life.”

Many students can’t make it all the way through. Research shows that students who require remedial education are less likely to earn a degree than students who don’t require remediation.

Lockett can attest to this. She still remembers when her first remedial class instructor challenged her classmates to continue and make it to the finish line. Many of her classmates went on to the next remedial course with her. But when Lockett finally got her degree, those students didn’t share the stage with her.

“None of my friends were behind me,” Lockett said. “None of the people that I knew. It was just me. And I felt really, really accomplished.”

This story was part of a collaboration between FCIR.org and StateImpact Florida. The award-winning series were published on December, 2012.

13th Grade: Older, Returning Students Strain Florida’s College System

By Lynn Waddell and Mc Nelly Torres

Pepper Harth has always loved music. After high school, she studied voice and acting in New York. Her life took several turns. She married, had three children, divorced and sold real estate in New Jersey. She moved with her children to Seminole, Fla., in 2007. Work was not as plentiful in Florida as she had expected. She got by singing at nightclubs and weddings.

About This StoryThe series “13th Grade” is the result of a collaboration between the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and StateImpact Florida. Related |

Last year, at 49, the single mom decided she wanted to do something more with her musical talents. Harth applied for federal financial aid and enrolled in the music degree program at St. Petersburg College in Seminole. Now 50, she aspires to use her future degree to practice music therapy in the health care industry.

Harth’s plans were set back, however, when she took the placement test that all Florida students must take before entering community college. She failed the math section. She wasn’t surprised: Math was never an easy subject for Harth in school, and that was more than 30 years ago.

Failing the math section didn’t mean she couldn’t go back to school. But it did mean that she had to take two remedial math courses before she could move on to college-level algebra. Actually, that turned into three semesters of remedial classes — she had to repeat one course.

Because the remedial courses don’t count for credit toward her music degree, Harth’s educational journey will take longer than she expected. It’s increasing her student loan debt –three-hour courses cost in-state residents between $300 and $350 at St. Petersburg College. And it’s costing Florida taxpayers who subsidize higher education, as well as federal taxpayers who support her Pell Grant.

There are a lot of people in Florida going through what Pepper Harth is going through. Remedial classes in math, reading and writing are seeing a surge of students at Florida’s 28 community and state colleges — schools where all students are welcome as long as they have a high school diploma or G.E.D. From 2004 to 2011, Florida’s remedial education costs for both students and schools ballooned from $118 million to $168 million.

The vast majority of students in these “developmental courses” are in some stage of going back to school after a break. An analysis by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and StateImpact Florida found that in the 2010-11 school year, 85 percent of students taking remedial classes were age 20 or older.

The trend with older students has been building for some time, but was accelerated by the Great Recession. Laid-off workers and those like Harth, who want to train for new lines of work or bolster their résumés, have been flooding onto college campuses. It isn’t just the weak job market that has been encouraging them to do this. The federal government is providing record amounts of financial aid.

When they get to campus, however, many find that their basic skills in math, reading and writing have deteriorated to the point that they are too rusty to take college-level courses. That’s especially true with math. Four of every five first-year, full-time students over 20 had to take remedial math courses, according to the 2011 Florida College System Readiness report using 2009-10 data. For those age 35 and older, the rate increased to 90 percent.

Hunter R. Boylan, director of the National Center for Developmental Education, says older students’ need for remedial math is natural. “You read every day, but when was the last time someone said, ‘Excuse me, Can you help me solve a polynomial equation?’ ” Boylan said. “It’s a skill that atrophies quickly and because it is not used regularly, it goes away.”

Back to School

Historically, college enrollment by older students peaks during economic downturns. This recession is no different — except the spike is higher and more federal financial aid is available.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 created the biggest boost in federal student financial aid since the G.I. Bill. Federal funding for grants and student loans has continued to climb under President Barack Obama, who has promoted easier access to education for the underprivileged and minorities. Funds available for the Federal Pell Grant Program, the largest form of federal aid that students do not have to repay, grew by more than $15 billion.

In Florida, students gladly took up the offer of more generous financial aid. As college enrollments shot up, so did the number of students requiring remedial classes. In 2007, the number of students who received federal financial aid and also required remedial work was about 48,000. By 2011, that number had more than doubled, to 97,000. Indirectly and inadvertently, the new federal dollars placed a greater demand for remediation courses on Florida’s community colleges.

Older students taking remedial courses said the availability of financial aid was a determining factor in deciding to go to college.

José Ramos is one of them. Ramos is a phlebotomist — that’s the person who takes blood samples for health tests. A Pell Grant enabled Ramos, 46, to pursue a nursing degree at St. Petersburg College. “Being the only provider in a household and for what I make, you can’t survive and go to school,” said Ramos, a father of four. “Normally, right now, I wouldn’t be in school. I’d be working two jobs supporting my family and not able to see my son grow up like I did my daughter.”

Ramos says he can earn more with a nursing degree and spend more time with his family.

Financial aid allowed Ramos to reduce his hours at work and concentrate on his studies. But his education has also taken longer than he anticipated due to his need for remedial math. Ramos didn’t score high enough in math on the entrance exam to take college-level algebra. Like Harth, he had to take remedial math courses and repeated one. He spent hours studying in the college’s learning lab in order to pass.

“I was disappointed and I hated to repeat math,” Ramos said of learning that he had to take the remedial courses. “But I guess it’s part of any job because no matter what you go into you are going to be using math. I just don’t think you will be using X’s and Y’s unless you are in something like engineering.”

Burning Out

St. Petersburg College reading instructor Patricia Smith oversees the campus learning lab where Harth and Ramos have regularly studied and received tutoring. Smith considers them success stories — they’ve persevered through the remedial classes and continued on with their studies. That’s not the case with many older students who have to take developmental classes.

Nationwide statistics on the drop-out rate of older students who require remedial courses are not available. In 2007, Florida’s Office of Program Policy Analysis & Government Accountability reported that 48 percent of all remedial students don’t complete all of their college prep courses, let alone graduate. Anecdotally, instructors say the rate is higher among older students.

Older students have any number of reasons for dropping out. That can cloud the picture when it comes to determining whether all the taxpayer dollars and class time spent on remediation is worth it.

Some laid-off workers find new jobs and no longer have the time or inclination to stay in school. Older students also typically deal with outside stresses such as childcare and work. In recent years of recession and war, Smith said, she has taught homeless students, war veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and single parents fighting eviction from their homes.

As Smith sees it, even though many students don’t complete their programs, the ones who do make the added expense and instruction worthwhile. “A lot of them are diamonds in the rough and could go on to do better things,” she said. “We might be the last people our students ever see who encourage them to keep them going or turn them off from education. We have a huge amount of pressure on ourselves to turn out students who are learning more, and not just making passing grades, but to make it in the work force because if you can’t read properly how are you ever going to make it as a nurse?”

Even though older students often have greater needs for remediation, Smith and other instructors said they typically are more focused and determined to succeed than younger students. “They know it’s their last shot at something,” Smith said. ‘They will be more focused and they will help bring up the younger students in the class and actually act as nurturers and be great role models for younger students.”

Never Too Late

Harth said she’s more driven in her studies now than when she was younger. Returning to school later in life has been hard. “I tell everyone go to school while you are young because it is really difficult when you are a single mom and have had many, many years out of school and there is so much other stuff in your head.”

She’s utilized all of St. Petersburg College’s resources — the instructors, the advisors, the learning lab, the tutors and study groups – to help her get through her courses, particularly math. “The support here is unbelievable. But you have to work at it. You really have to be self-disciplined.”

Although it’s not required, she sees an academic advisor every semester to make sure she is on the right path with her courses.

Now that she’s completed her remedial math coursework, she’s tutoring students in other subjects and expects graduate in 2013. “I used to think I was too old to go back to school, but now I say never give up. It’s never too late.”

This was the last in a series of stories published on December, 2012. The award-winning series were part of a collaboration between FCIR.org and StateImpact Florida.

School of Hard Financial Knocks

By Mc Nelly Torres

As part of the 2009 economic stimulus package, millions of federal dollars flowed to Florida’s public school districts. The money was intended to benefit low-performing schools as way of closing the so-called achievement gap.

Though President Obama’s ambitious education agenda included saving teachers’ jobs and renovating classrooms with funds from the economic recovery bills, his vision was also to accelerate improvement in schools.

“Every dollar we spend must advance reforms and improve learning,” U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said in 2009. “We are putting real money on the line to challenge every state to push harder and do more for its children.”

But with the aid of federal waivers, school districts were allowed to divert money from education reform to patch holes in general operating budgets. In fact, a review of financial records by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting shows that the state’s school districts spent more than $890 million in federal money this way.

Starved for cash as a result of plummeting real estate values and dwindling property tax revenues, Florida school districts used these hundreds of millions to put off the inevitable — difficult budget cuts.

Now, two years after the first stimulus dollar rolled in, Florida’s public school system is learning difficult financial lessons. School districts throughout Florida are laying off teachers, closing programs and scrambling to identify other significant cost-saving measures — all problems made worse by the fact that Florida’s school districts used the stimulus money in large measure to delay needed cuts.

A lesson in school finance

The financial problems for Florida’s public school districts began in 2007, when shrinking local tax revenues and declining state resources, including $1.4 billion in funding cuts to public schools, created budget deficits of tens of millions of dollars.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, better known as the stimulus bill, came to the rescue, channeling an unprecedented $100 billion into the nation’s education systems — with $4.7 billion sent to Florida — to stabilize school districts and stave off layoffs.

The cash infusion carried with it an ambitious goal — to speed up academic improvement at low-performing schools. The federal government labeled part of this money as Title I, meaning it was to be earmarked for programs to improve academic achievement among low-income students.

But Florida’s largest school districts used more than half of the Title I money to pay for salaries and benefits during the 2009-10 school year. More than $218 million of the $404 million granted to Florida’s 14 largest school districts was spent to help keep the schools afloat.

Nationwide, the total number of waivers allowing schools to divert Title 1 money to other budgetary needs was unprecedented.

In 2009, after the initial release of stimulus money, Education Secretary Duncan granted 351 waivers to districts nationwide that allowed their administrators to use Title I money for other purposes. The Education Department issued just 51 waivers in 2008 and 35 in 2007.

In one example, 7 of every 9 school districts in Florida received waivers that gave administrators flexibility to use the extra dollars intended for school choice, transportation and tutoring to pay teacher salaries and benefits.

Cheryl Sattler, a Quincy, Fla.-based consultant who works with public school districts nationwide, said the federal government was not clear about how the money should be spent.

Some predicted this outcome. A 2010 study by Bellwether Education Partners, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C., warned that the redirection of stimulus money wouldn’t address future funding shortfalls.“Over and over, the feds said don’t spend [stimulus money] on people, but at the same time, they gave this message that the whole law was about saving jobs,” Sattler said. “You kind of have to pick.”

“The money is going to run out and school districts need to look more closely at how they budget, which they’ve never done before,” said David DeSchryver, vice president of education policy for Whiteboard Advisors, a Washington, D.C.-based group that focuses on public education policy. “They have basically laid out programs and gone mindlessly about their business.”

Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators, said the recession has hit education funding harder than most education administrators anticipated.

“The intention for the stimulus funding was for school districts to use those additional dollars for improvement and reform,” Domenech said. “The reality in most states was that those dollars were basically used to replace state and local dollars that were cut from the education budgets.”

Now, the stimulus funding is about to run out — and the economy in Florida shows no sign of improvement.

Meanwhile, the state government slashed the education budget even further. During the 2011 Legislative session, legislators cut $1.1 billion from education — or $542 per student.

How local districts are faring

The Obama administration wanted the stimulus money to provide financial incentives for teachers with a record of helping students achieve in historically low-performing schools. Two school districts in Florida did just that.

“The teachers, in order to get this money, have to perform well,” said Kathy LeRoy, chief academic officer at Duval County Public Schools. “The biggest impact on the student success is the teacher in the classroom.”

How Districts Obtained Federal WaiversFederal education funding aimed at supplementing low-performing schools usually comes with strings attached — rules for how the money should be spent. That’s especially true with Title I funding, whose purpose is to help academically struggling students in low-income schools. Federal law mandates that school districts spend at least part of their federal money on tutoring, transportation and other services for students attending failing schools. But in 2009, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan invited states to apply for extra money made available as part of the economic stimulus package. Although the Obama administration said publicly that the money should go toward education reform initiatives, jobs were also a priority for the administration and waivers allowed districts to use the money to cover salary shortfalls and fill other budget holes. To obtain waivers, districts submitted proposals stating how the money would be used and outlining the manner in which schools will continue to provide assistance to Title I students served by the programs for which the waiver is requested. Most states jumped at the opportunity to receive these stimulus dollars. Only one state — Vermont — did not submit an application for a waiver. The Florida Department of Education, by contrast, requested 11 different types of waivers. On Nov. 19, 2009, the U.S. Department of Education granted waivers to allow Florida’s schools to bypass six different types of federal requirements, giving school districts the flexibility to use the funding elsewhere. The most requested waiver in Florida involved the federal requirement mandating that school districts spend a portion of federal funds on school choice, transportation and tutoring for students in low-performing schools. The waiver provided more than $428 million in taxpayer dollars for 62 school districts. Since then, school districts have submitted amendments to their proposals, primarily to fund salaries for teacher and reading and math coaches as well as to provide teacher training, purchase equipment and supplies. |

For the 2010-11 academic year, Duval received $4.1 million in federal money, which provided financial incentives to 1,982 teachers in 28 low-performing schools.

But as many Florida school districts did, Duval also found ways to attract extra money from the federal government. Administrators at the Jacksonville-area education system pointed to 11 high schools and nine middle schools and added them to their list of Title I schools, bringing in an additional $5.8 million in stimulus money that paid for salaries and benefits for teachers, as well as for supplemental staff such as reading and math coaches. Administrators also used part of this funding in combination with other funds to offer professional development courses for teachers.

Despite stimulus funding, Duval County Public Schools is currently experiencing significant financial problems, including a $97 million budget shortfall for next school year.

Duval school board members announced in June that they balanced the budget. Teacher and staff furloughs, expected to save the district $7 million, accounted for the largest portion of the cuts.

Administrators for Hillsborough County Public Schools, by contrast, recognized from the beginning that stimulus funding would end. Though the district is still feeling the sharp economic pinch, Hillsborough used its $6.5 million in Title I funding to offer incentives to 1,650 teachers at 40 schools for two academic years — 2009-10 and 2010-11.

“That cliff is coming after two years and the money will be gone,” said Jeff Eakins, Title I director of Hillsborough County Public Schools in Tampa. “And that’s why we looked into those one-time investments that will have long-term impact.”

Two years ago, Miami–Dade County Public Schools Superintendent Alberto M. Carvalho supported the state’s decision to seek the waivers. In a July 17, 2009, letter, he urged state education officials to apply for “all allowable waivers for Florida schools in order to maximize flexibility school districts needed.”

The financial outlook for Miami-Dade, the nation’s fourth-largest school district, didn’t seem bright when Carvalho wrote the letter. His school district had gone through more than $300 million in cuts, with more to come later that year.

Even though Miami-Dade County Public Schools leaders used some stimulus money to enhance Title I programs and offerings — such as student access to technology, online and hands-on math and science programs, and training for teachers — most of Miami-Dade’s $96 million in Title I funds paid for salaries to retain and hire staff.

“I think that many of the successes and good things that happened during the past three years would have not happened had those dollars not been there,” said Magaly C. Abrahante, a Miami-Dade assistant superintendent overseeing Title I programs, referring to how Miami-Dade was able to expand Title I programs and offerings.

Asked if she thought federal education officials’ expectations for reform were unrealistic, Abrahante admitted that Florida’s economy has prevented school districts from using the funds for their intended purpose.

“I think to some extent the financial situation has been a distraction,” Abrahante said. “And under the circumstances, districts have done what they had to do to keep the schools running.”

Miami-Dade, where 72 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced lunch, is in better financial shape than most school districts in Florida. That’s largely because Miami-Dade’s administrators have made extensive changes to the budget, including salary cuts for top administrators, principals and school police supervisors. In addition, funding was slashed for clerical and transportation services, as well as for programs aimed at troubled teens.

Without doubt, most school districts in Florida are in worse shape than they were two years ago, when the stimulus money first arrived.