BY MC NELLY TORRES

In the two years Patrick R. Newman lived in South Florida, he bought and sold more than a dozen condos — flipping some several times within hours or days — in a mortgage fraud strategy that allegedly duped a bank into approving millions of dollars in questionable loans.

Newman died in 2006, as FBI authorities were investigating his multimillion dollar condo-flipping operation. Now, National City Bank — the lending institution that approved more than $14 million in mortgage loans that ultimately were defaulted on — is suing several attorneys, appraisers and businesses who the bank contends assisted Newman.

In three separate lawsuits, filed in U.S. District Court in March 2008, bank officials allege Newman’s associates helped carry out a scheme that resulted in losses to the bank. The defendants — Melbourne attorneys Charles A. Schillinger and Christopher J. Coleman, appraisers Mary K. Gibson and Douglas E. Lightcap and the Atlantic Hotel Condominium Association where Newman was a board member — deny the allegations.

The bank is seeking an unspecified amount to cover the losses.

The Newman case spotlights a trend many legal experts predict will escalate in coming months. They expect a surge in litigation as more banks try to recover losses caused by what they contend was mortgage fraud. This is especially true in Florida, which ranked among the top three states in mortgage fraud the past three years.

“Many of these cases end up in foreclosure with the bank swallowing the cost,” said Michael J. Sichenzia, a mortgage fraud expert for Dynamic Consulting Enterprises, a Deerfield Beach mortgage modification consulting firm.

As banks relaxed loan standards at the peak of South Florida’s real estate market several years ago, unscrupulous loan applicants, mortgage brokers, appraisers and title attorneys found it easier to pass false or doctored information to have loans approved, legal experts say. Some inflated a buyer’s income or conducted fraudulent property appraisals.

“It became a systemic problem,” Sichenzia said. “That’s when millions of bad loans were approved.”

And as the housing market collapsed, local, state and federal law enforcement officials began investigating a growing number of mortgage fraud allegations.

Since 2007, many states have toughened laws in such cases — including Florida, where mortgage fraud is now a second-degree felony.

Mortgage fraud has wide-ranging effects on communities. When properties are foreclosed, surrounding home values depreciate and neighborhoods sometimes deteriorate. The Mortgage Asset Research Institute, an industry group, estimates 80 percent of foreclosures involve some type of mortgage fraud. And it has been a significant factor in the unprecedented number of foreclosures nationwide and in South Florida, according to the FBI.

Nationwide, mortgage fraud causes annual losses of more than $6 billion, the FBI estimates.

Kathleen Day, of the Center for Responsible Lending, a consumer advocate group, said lenders are at fault too because good lending practices went out the window and loans became accessible to everybody.

“Then you have all these bad actors coming into play because they see a way to profit,” said Day, who also teaches real estate ethics at Georgetown University.

In South Florida, at least 139 people have been prosecuted on charges of mortgage fraud in 36 cases in the past three years — involving more than $224 million in loans, according to Alicia Valle, special council for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Miami.

Mortgage fraud has cost banks and property owners in South Florida hundreds of millions — if not billions — of dollars, said Glenn Theobald, chief legal counsel for the Miami-Dade Mortgage Fraud Task Force.

The Newman case offers a glimpse into flipping.

Between 2004 and 2006, Newman bought 14 properties at the Atlantic Hotel Condominium in Fort Lauderdale and two at Toscana Condominium in Highland Beach, the lawsuits said. He then flipped the properties quickly, making more than $11 million in profit, court documents show.

The bank foreclosed on all the properties. Scott L. Cagan, an attorney representing National City Bank, said he couldn’t comment on pending litigation.

Kathy M. Klock, an attorney representing Atlantic Hotel Condominium Association and two board members — Gregory Lazon and Steve Hundley — said the suit is frivolous.

“The bank is acting as if they don’t bear any responsibility in this,” Klock said.

Newman, a real estate investor, moved to South Florida from Brevard County in 2004. Through mutual friends, he met more than a dozen people and allegedly persuaded them to pose as condo buyers. He promised those buyers that he would pay the mortgage, taxes and association fees before selling the condos after a short period of time, the suit contends.

Newman created several companies to handle the transactions — listing himself, Schillinger, Coleman and a friend as registered agents. The suit contends Newman used the network to buy and sell the condos, eventually selling them at inflated prices, as the bank approved the loans.

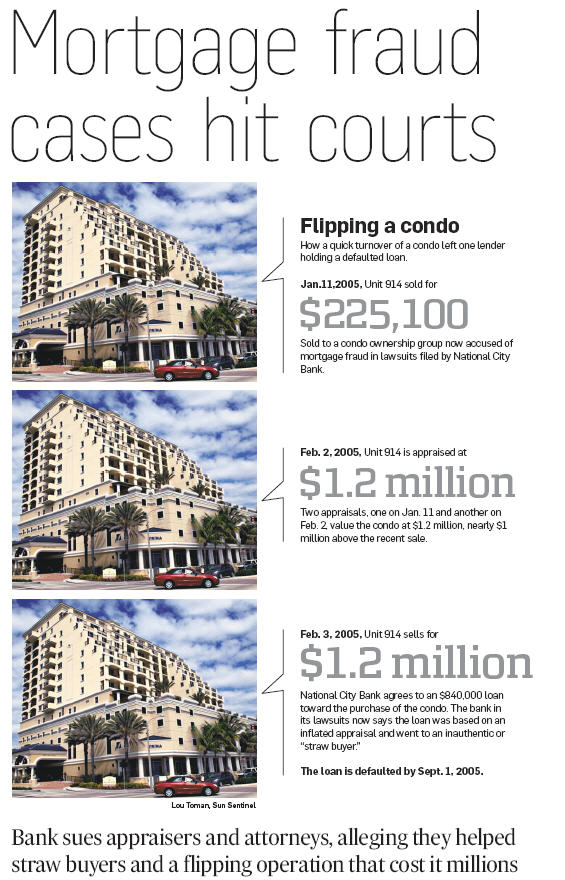

For one of the Newman properties — Unit 914 of the Atlantic Hotel — National City Bank approved an $840,000 loan to a straw buyer, the lawsuit alleges, and the property closed Feb. 3, 2005 — weeks after two separate appraisals valued the unit at about $1.2 million. It was the fourth closing on the property in less than a month.

According to the bank lawsuit, the two appraisals on which the loan was granted vastly inflated the value of the condo unit. The two appraisal companies performed all the appraisals. Attorneys representing appraisers Gibson, of Brevard County, and Lightcap, of Delray Beach, said their clients deny the allegations that they inflated the property values.

The condo was first sold for $225,100 on Jan.11, 2005, to a company known as The Formula and later conveyed by quitclaim deed to Entella Holdings Foundation. Schillinger — a defendant in the suit — is the registered agent for Entella, records show.

Entella transferred ownership of the property by quitclaim deed to MLK Development Investment on Feb. 3, 2005. That day the unit was sold to a straw buyer for $1.2 million.

Coleman, another defendant in the suit, is listed as one of the registered agents of MLK Development Investment. The loan was defaulted on by Sept. 1, 2005, records show.

In court records, Schillinger and Coleman acknowledged they conducted the closings, but they said they had done nothing wrong.

“The proceeds of a mortgage loan from the Plaintiff were used to finance the acquisition of the subject property,” court records state.

Attorney Gary R. Shendell, representing Schillinger and Coleman, said: “My clients strongly denied the allegations, and they will be exonerated after this litigation is done.”

On Oct. 3, 2006, Newman was found dead at a Boca Raton hotel of an apparent drug overdose, autopsy records state.

He was 34.

As the cases move through the legal system, the bank, title attorneys and straw buyers have filed claims on Newman’s estate seeking money.

James Facciolo, an attorney representing two of the alleged straw buyers, said Newman’s dealings seemed like a Ponzi scheme: He was making mortgage payments for a while, with money coming in from new deals and new loans.

“My clients had excellent credit before these foreclosures,” Facciolo said. “Now their credits are ruined.”

The South Florida Sun-Sentinel published this story on Sunday March 22, 2009. Mc Nelly Torres was a consumer/watchdog reporter for the Sun-Sentinel from 2005-2009.

Foreclosure rescue plan? Be cautious

You could be signing away control over your home

May 21, 2007|By Mc Nelly Torres and Jon Burstein Staff Writers

SECOND OF TWO PARTS — They thought the postcard came from an official government agency. The mailing from the Florida Housing Council, a South Florida foreclosure rescue firm, promised to help save their homes.

James and Teresa Johnson, parents of three children, said the firm gave them hope when they were about to lose their three-bedroom house in West Palm Beach.

Stroke victim Roy Hull and his wife Connie sought the company’s help when homeowners association fees threatened to push them into foreclosure in Pembroke Pines.

And Cuban immigrant Hector Irizarry and his wife, Olevene, called the number on the card when they fell behind in their mortgage payments on their modest ranch house in Miami.

All three couples said they signed FHC documents without scrutinizing them. They say they trusted Jack Moussa, the registered agent of FHC, who promised to help them avoid foreclosure. And they say they signed documents without knowing their signatures gave control and, in some cases, ownership of their properties to FHC.

“How do you start all over again when you are in your golden years?” asked Connie Hull, who worries that she will lose her home. “Our house means everything to us.”

Moussa denies any wrongdoing.

“These are people who have made a commitment,” Moussa said in an interview with the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. “But they don’t want to live up to it. They want to invalidate our agreement by calling it something else.”

The dispute comes at a time when South Florida’s mortgage delinquency rate has significantly increased. Foreclosure filings — initial notices sent by mortgage companies indicating late or delinquent payments — in South Florida have jumped 30 percent, from 43,402 in 2005 to 56,273 last year, according to RealtyTrac, a national company that tracks foreclosures.

Nationwide, homeowners have increasingly responded to foreclosure rescue offers, according to a report conducted by the National Consumer Law Center, a Boston-based consumer advocacy group. Some rescue firms, the report said, use pressure tactics, telling homeowners there’s little time left to act while keeping them in the dark about the legal process and their rights.

“There’s a lot of abuse like this going on,” said William Sklar, a legal specialist in real estate who teaches at the University of Miami School of Law. “We need some legislation to stop some of these practices.”

Consumer advocates say many homeowners don’t understand the complexities of real estate law or how to check the background of a company that promises to save them from foreclosure. Foreclosure rescue companies are not licensed by the state or county, so it’s unclear how many operate in South Florida.

FHC and Moussa have faced seven lawsuits — one was settled, six are pending — in Broward, Palm Beach and Miami-Dade county courts in the past three years alleging fraud and deceptive practices. Homeowners in four cases said Moussa told them FHC is a federally funded agency that helps homeowners in financial distress.

In at least two cases, it is alleged that Moussa met with homeowners by himself, asking them to sign documents, yet records show witnesses and a public notary were present. The Johnsons and Irizarrys said he sold their homes without their consent.

“When I saw the card I thought that it was a government program,” James Johnson said. “I was thinking about refinancing, but the card mentioned all these programs, so we thought this would be a good option.”

According to Moussa, homeowners on the brink of foreclosure and who are now suing FHC signed several different kinds of agreements.

In some cases, homeowners created a trust partnership agreement between them and FHC, under which the company promised to clear existing debts, Moussa said. Under the trust’s terms, Moussa said the homeowners agreed to send mortgage payments to FHC for a year, but to regain ownership, they need to pay all the money advanced and 50 percent of the property’s increase in value within that past year.

In other cases, homeowners signed a purchase-lease agreement that sold the properties to the FHC, Moussa said.

Before taking over the FHC, Moussa ran the Foreclosure Assistance Bureau in Fort Lauderdale, a company that promised to help homeowners ward off foreclosure, court and state records show. Bankruptcy court records indicate that in 1994, customers accused Moussa of leading clients to believe the company was a government agency.

Moussa denies making such claims.

The Florida Bar investigated Moussa three times — in 1993, 1996 and 2001 — for suspected unlicensed practice of law related to foreclosure and bankruptcy matters. Each time he settled the complaints without admitting any wrongdoing.

“Mr. Moussa is not an attorney, never claimed to be one or being engaged in the practice of law,” said Adam Skolnik, an attorney representing FHC and Moussa.

Moussa, 55, said FHC provides financial assistance to homeowners. He describes himself as a managing member with Florida Housing Council. Moussa is listed as the registered agent for Equity Investment Capital Management Inc., the company that owns FHC.

Former FHC clients and their attorneys said Moussa has created even more financial uncertainty for them.

“I think the Florida Housing Council is taking advantage of people who are in a desperate situation,” said David Silverstone, an attorney who recently settled a case against FHC and has another pending. “They are saying one thing and then presenting papers that show something else. It’s hard for even an attorney to get through these documents.”

Hector Irizarry said he stays awake most nights worrying about his family’s future. “I feel betrayed,” Irizarry said in Spanish. “He [Moussa] came to my home and befriended my grandson. He said he could help us get out of foreclosure and fix the house, but it was all a lie.”

The South Florida Sun-Sentinel published this article on May 21, 2007.

FAMILIES LEARN BITTER LESSONS

Couples put at risk the homes they tried to save

The Johnsons

James and Teresa Johnson ran into mortgage problems in mid-2004 after their homeowners insurance was canceled because they missed payments. James, 43, who works for Palm Beach County Schools’ maintenance department, was thinking of refinancing the three-bedroom home they bought in 1994 for $44,100.

That’s when the Florida Housing Council postcard arrived in the mail.

The Johnsons said Moussa told them to place their home in a trust for a year, make their mortgage payments through

FHC and pay a $50 monthly fee. In return, the firm would pay off their debt and also provide needed home repairs.

No notary was present when Moussa arrived at their home, the Johnsons said. Yet records filed with the Palm Beach

County Clerk’s Office show a notary and two witnesses signed the documents Aug. 3, 2004.

The Johnsons signed documents that gave Moussa control over their property. County records show the deed of ownership passed to FHC and Moussa and then to Carlos Alonso, who bought the property Feb. 11, 2005.

The Johnsons filed suit against FHC and Alonso Nov. 23, 2005.

Moussa said he bought the property from the Johnsons, and rented it back to them. “I’m entitled to sell the property and they [Johnsons] were aware,” Moussa said.

Alonso denies any wrongdoing, according to his attorney John Hart. Alonso, he said, has no affiliation with FHC.

“I felt betrayed and angry,” said James, who works for Palm Beach County School’s maintenance department.

“This house means everything to us.”

The Hulls

Roy and Connie Hull lived in a trailer home for years before buying their dream house. But in 2003 Roy Hull, 63, a truck driver, suffered a stroke, which paralyzed his left side, and could no longer work.

The couple had to rely on Connie Hull’s salary as a human resources director.

By February 2005, the Hulls had fallen so far behind in payments to their Pembroke Pines homeowners association that they were facing a court judgment of about $15,000. FHC’s card arrived in the mail.

“I thought that God answered our prayers,” said Connie, 52. Moussa and a public notary came to their home March 29, 2005.

The couple signed documents Moussa presented that the Hulls said they thought would pay off their $15,000 debt and prevent foreclosure on their home, appraised at $513,000.

“We thought we were getting a federal loan,” Connie said.

The Hulls said they tried to get out of the deal months later, but Moussa said it would cost them $160,000 — 50 percent of the accumulated equity for that past year.

The couple filed a suit against FHC in September 2005.

Moussa said the homeowners are suing because they don’t want to fulfill the terms of the agreement.

— M C N E L L Y T O R R E S A N D J O N B U R S T E I N

The South Florida Sun-Sentinel published these articles on May 21, 2007. Florida Attorney General sued Florida Housing Council, Equity Investment Capital Management Inc., the company that owns FHC, and Jack Moussa in 2008. Connie Hull, who filed a complaint with the attorney general’s office, died in October, 2007.